|

|

Speed in Freefall

For some time now, there have been scattered partisans of an absolute form of freefall who have been playing vertical, high speed and solo, jumping from an altitude between 3 and 4000 meters. With a taste for personal challenge and a small taste for competition, they can now move towards speed competitions in freefall

T e x t s a n d P h o t o s b y M i c h e l P i s s o t t e

A then very young skydiver, Bruno Gouvy tried to slash air, drawn by a nose cone weighted with 50 kg of lead. His goal was 950 kph, according to his rigorous calculations made based on his engineer's training. After 4 attempts from between 10 and 12 000 meters, he was credited with a 539 kph speed, measured by the radars of the Centre d'Essais des Landes military test range.

On the basis of the echoes from/of contests organised in the USA, Didier and Mike have thought of " speed " in terms of affordable altitude and regular equipment (cone and oxygen being forbidden)

The story is short. During the 99 American spring, audible altimeters manufacturers collaborated to the organisation of races. Their hardware, used with the right software, allowed the measurement and the memorisation of new parameters, among which the vertical speed.

In Sebastian (Florida), Cool & Groovy proposed the Evolution 2000 that allowed the winner, Chris Lynch, to post a 418 kph speed. In Deland, Larsen & Brusgaards proposed the famous Pro-Track, a small jewel of advanced data processing. John Arne Løken won with an average speed of 439 kph over one mile

Norway, that has a taste for risk (see the ski jump culture), tried to organise three speed competitions in 1999, up there in the north of the North. Bad weather prevented the first one, the second one in Voss gathered 4 competitors... resulting in the cancellation of the third one. Since then, Norwegians decided to go nicking prizes elsewhere in the world.

Not in England though where was organised in Hibaldston in July 99 a race using Evolution 2000, only " brits " (home sweet home) entered the contest with 24 competitors including 2 women. Jude Haig, a young student in social medicine, won the women contest with a 226 mph average speed. She has made a total of 250 jumps, she went from AFF to freeflying and doesn't know the meaning of the word RW. Ian Chapman, aka Chapi, 3 200 jumps, AFF and tandem instructor, went at 260 mph (the reader will have to make the conversion to "normal" units).

For our fellows in Gap, it was obvious that the speed idea could only be imported in France with a 1 000 meter race (a good republican kilometre). It was a good idea; it appeals to the media.

The general public can associate quickly enough summits ,which make it shiver every winter on TV, with these speed giants. They form a small tribe, with women and men who have been rushing down impressive slopes in a perfectly controlled position for about twenty years.

It is also what Ken Hansen, from Norway, thought when he started skydiving in 1985. Ten years later, he read in the US monthly magazine Skydiving that " Charles Brian had passed the 500 kph barrier, as measured by a Skycorder prototype "

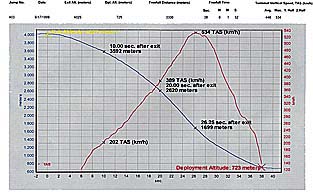

The French-speaking skydivers on the internet know that in Avignon some high speed fans flirted with the 400 kph and that Geraud Tellier went to a 470 kph top speed in June 99. The principle in Gap was to measure the average speed between 2 600 meters and 1 600 meters, a true kilometre with an exit at 4 000 meters and an imperative stop of the dive at 1 200 meters under pain of exclusion without return. There comes Niels Brusgaard and his top notch computer machinery. PC, mouse, colour printer, software, numeric camera, cables and a ProTrack for the competitors to strap to their ankle. After the jump, Niels displays the speed curve as measured by the ProTrack and the computer calculates the average speed between the 2 chosen altitudes. The competition being a test, there was a maximum of freedom left in the rules. After the end of Friday morning briefing, participants were suggested to jump as much as they were able to, only the best performance being kept for ranking on Sunday evening.

This is how Philippe Valois could jump on Friday and leave for Vincennes to the accuracy French championship finals for the weekend. On the other hand, Philippe Tinet, Benoît Roussel and Pascal Passard could only play on 1 to 3 jumps on Saturday afternoon, Sunday seeing low clouds coming without hope for a jump.

One leaves the plane as one wishes, floater, diver, or even in a ball position as Jude. One gets (or thinks one is) vertical (90° !) from an intoxicating track. Letting a leg or hands drag is out of the question. Tucking everything to have as low a CX as possible is necessary. Vertical can mean head down or head up, for instance Fabienne Brooke made the competition jumps standing up. The helmet opens the air, shoulders hugely widen it and air should stick as close as possible to a straight body, with arms and legs tightened, the whole body tonic and linear up to the toes. The ideal would be to slide into a vertical air tube of constant diameter, every oscillation being a brake and involuntarily going through the air wall promises a " giga tumble ".

There is the 350 kph gate, the 450 kph barrier and the very restricted 500 kph club.

The first jumps can be disappointing: one has the impression of being vertical, well in position, whereas the parasitic arch of the belly flying experience leads to an ultrafast track.

Curiously, it is difficult to be constant in one's performances, no one escapes, on one jump or the other, the arch-braking that is so difficult to counter when one is installed in this position.

A priori, style addicts and freeflyers are better armed to get vertical. They dive and fly easily in the 300 kph zone (says ProTrack). But holding a constant acceleration is the key.

Collectors of ParaMag issues can get an idea of what I mean by looking at the very good photos on the covers of the September 1990 issue featuring Maryvonne Simon shot in an absolute dive by François Rickard and of the August 1994 issue with Thierry Butzbach, in light backtrack, photographed by Bruno Passe.

What one feels at 300 kph in this situation is as difficult to express as what is lived on a first jump. The word on every mouth is: adrenaline. Tense muscles towards the ground that invades the field of view, all the comfortable references topple, great ! How does one leave this position? The fastest ones, therefore the more exposed, explain that they first move to a tracking position before anything. After that, it is necessary to go flat for some time to decelerate and to get a reasonable opening. This is quickly learned, for the comfort. This vertical flight turns you on, all the opposite of a contemplative wingsuit jump. Be careful as, at speeds over 500 kph, the last 1 000 meters last hardly 7 seconds. What future is there for this discipline? A personal curiosity. Why not imagine dealers renting ProTracks for 10 FF a jump ? One could then know one’s worth. But be careful again, a speed jump must be prepared. On the equipment side, it is necessary to take care of everything: well tucked elevators, containers well closed by firm loops, pilot chutes and reserve handles correctly set in their lodgings, rubber bands and velcros in good shape. As for the helmet, the audible altimeter should be as close to the ear as possible and a flashing device is a good thing. The AAD should be on. Nothing must float, the harness very adjusted and the chest strap tight. A tight suit close to the body, or naked legs, although trousers make keeping a vertical position easier. The jump has to be thought in advance and not made because one slipped at the door and lost one's RW buddies. In Gap, 2 competitors would jump at each run at 4000 metres, leaving 10 to 12 seconds between each other. As in freeflying, beware of the track. The first jumper was followed by ground video and, surprise, if the dropzone is not too noisy one hears " something like the noise of a 100-way formation with a jet growl ", according to the skydivers there. But after the curiosity, will the activity become fashionable or will there be competitions? As for fashion, the discipline seems too technically demanding, so high-level international competitions... certainly. One already speaks of creating a league or a speed race pro-tour. There is room for media innovation, even though right now it lacks dive pictures. Hence, sponsors, champions, records and especially prizes! Advertisers or companies will be interested because the discipline is superb with simplicity and absoluteness. The style still makes the man and our time is lacking people who go serenely, right, quickly and straight. Do read what follows (in french...)

|

|

|

On September 17th-19th, On September 17th-19th in Gap-Tallard, Didier Boignon and Mike Brooke organised what was probably the first European speed competition in freefall. The number of participants was fairly limited (15 including 3 women) and yet the idea is as attractive as technically challenging.

We keep Bruno Gouvy's very daring " goal: speed " in memory (see ParaMag n° 40, 1989

On September 17th-19th, On September 17th-19th in Gap-Tallard, Didier Boignon and Mike Brooke organised what was probably the first European speed competition in freefall. The number of participants was fairly limited (15 including 3 women) and yet the idea is as attractive as technically challenging.

We keep Bruno Gouvy's very daring " goal: speed " in memory (see ParaMag n° 40, 1989